YOUNG EAP BLOG | PROTECTING CHILDREN FROM TOBACCO

May 11, 2018

The situation

Exposure to SHS leads to an estimated 166.000 child deaths each year worldwide, with most of those deaths resulting from lower respiratory diseases. Eighty-six percent (86%) of youth in Europe are exposed to SHS in public spaces. Following international studies, several European countries started implementing tobacco control in their federal laws by prohibiting smoking in public places. In March 2004, Ireland was the first country in the world to implement legislation prohibiting tobacco smoking in workplaces and enclosed public places. Many other countries in Europe have since then followed Ireland´s example. The implementation of smoke-free legislation has been found to reduce exposure to tobacco smoke; encourage people to quit smoking; improve adult health outcomes; and is associated with a substantial decrease in the number of perinatal deaths, preterm births, and hospital attendance for respiratory tract infections and asthma in children.

Failed efforts on smoking reduction: the Austrian case

Important steps to ban smoking from public places have also been taken in Austria, but failed to be included in national law. In 2004, the former Austrian health minister and representatives of the Ho.Re.Ca sector agreed on a voluntary commitment to install “smoke-free” areas such as restaurants, pubs, and cafés, in an effort to protect non-smokers. Further steps were taken and, in 2017, the former government announced an upcoming national law prohibiting smoking in public places. Following the last elections (October 2017), however, the current Austrian government stated that this national law would not be implemented, classifying the legislation as “repressive”. Many politicians from the former period, who had publicly spoken up against smoking in public areas, changed their mind and followed the current government’s decision, as an act of loyalty to their political party and the promises they made in the coalition with the FPö party.

This swing-state-of-mind of the government has led to a civil society outcry, especially among academic/medical experts, and a “Don´t Smoke” petition was created. This petition reached the 100,000 signatures mark (necessary for it to be discussed in the Parliament) after three days, and has gathered 591.146 signatures so far. In response, right-wing MPs declared that they still favour direct democracy, but will not officially enable it until 2021, due to bureaucratic reasons, and therefore will stand by their current position. The days before the legislation was voted down were marked by heated discussions. The current Austrian health minister, Beate Hartinger-Klein (FPö) stated that the proposed law would be detrimental to the Austrian hospitality sector and “gruesome”.

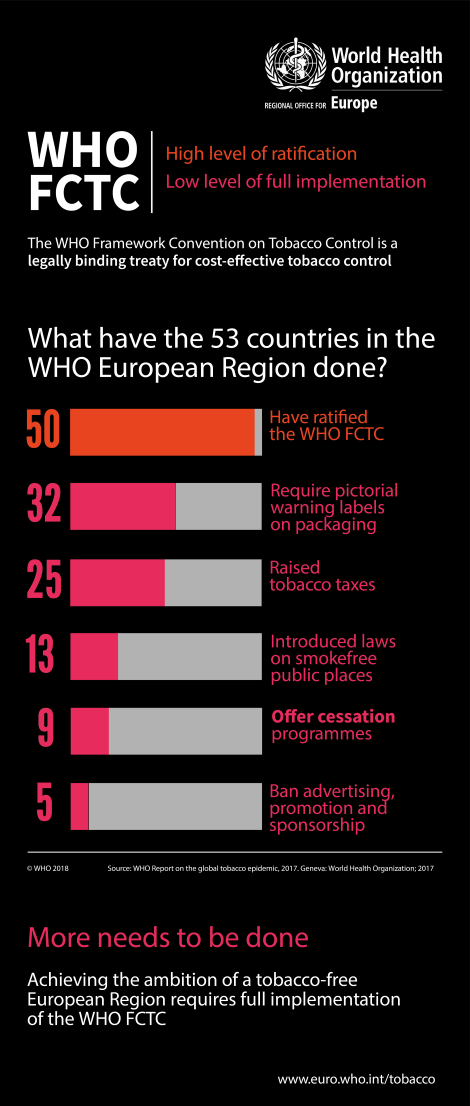

To protect adults and children from second-hand smoke and the temptation to start smoking, the World Health Organization has implemented the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2005. Austria is one of the 50 out of 53 countries in Europe that has ratified this Framework in 2005. The FCTC is not only foresees interventions like smoking bans, but also other effective measures on price and tax measures; packaging and labelling of tobacco products; sales to minors; and regulation of tobacco advertising and promotion. As the tobacco industry targets youth and children as replacement smokers, adherence to the Framework is important, as marketing efforts of the tobacco industry often influence adolescent smoking behaviour to a greater extent than it influences adult behaviour. In several European countries, tobacco use in adolescents is increasing; furthermore, in countries like the Czech Republic, Latvia and Lithuania, adolescent smoking rates are almost the same as adult smoking ones.

Even though almost all countries in Europe have ratified the FCTC, it has not been yet fully ratified by most. From 2006 to 2014, Austria ranked last in implementing tobacco control policies in comparison to all other 27 member states of the EU. This is sad, because not only smoke-free legislation is associated with substantial benefits to child health, but also because the majority of other policies included in the Framework also indicated a positive effect.

How are children and young people affected by smoking?

The effects of active and passive smoking on the health of children and adolescents are well known. Among young people, the short-term health consequences of smoking include respiratory and non-respiratory effects, addiction to nicotine, and the associated risk of other drug use. Long-term health consequences of youth smoking are reinforced by the fact that most young people who smoke regularly will continue to smoke throughout adulthood. Studies have shown that early signs of heart disease and stroke can be found in adolescents who smoke. Regarding SHS, a study showed that, in 2010, 11% of low respiratory infections, 8% of wheezing in children under 3 years of age, and 4% of asthma in 3–4-year-old children, as well as 22% of cases with meningitis, could be attributed to second-hand smoking in the UK. What’s more, one in five cases of sudden infant death syndrome can be attributed to exposure to SHS, as well as a substantial proportion of all hospital admissions. The greatest cause of SHS, especially for young children and (unborn) babies, is from mothers who smoke. Maternal smoking rates vary across Europe, ranging from 13% in Sweden to approximately 32% in Austria. New-borns are predisposed to increased respiratory morbidity after birth by exposure to SHS during pregnancy, something that also applies to non-smoking mothers. There is a strong association between active smoking during pregnancy and pre-term births, with a clear dose-response relationship.

Several tobacco control policies implemented in European countries (such as restrictions on smoking in public places, advertising bans, price taxes or the level of public information campaigns) are inversely related to perinatal outcomes, particularly pre-term births. As indicated by paediatric pulmonologist, Dr. Noor Rikkers, during a recent interview with the EAP, studies investigating the negative effects of third-hand smoke are scared. Despite the small amount of studies about third-hand smoke, however, paediatricians have to advise parents not to smoke outside, for children are very sensitive to the negative effects of tobacco, even to remnants of smoke in clothing. Likewise, health care providers who smoke probably expose children to an unintentional health risk.

Our recommendations

In conclusion, active or passive exposure to tobacco smoke is a major cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in (unborn) babies, children and adolescents. Neonates, children and adolescents deserve to grow up in a smoke-free world. It should be everyone’s goal to enable the first “smoke-free” generation; therefore, WHO´s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control needs to be fully implemented and followed as much as possible in all European countries that have previously ratified their measures.

Following EAP’s 2016 call for a Europe where children and adolescents are protected from second-hand smoke, Young EAP encourages politicians to take measures towards the first Smoke-Free Generation. As the EU (as a whole and each member state individually) has ratified WHO´s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), we encourage politicians to act accordingly and thus require pictorial warning labels on packaging; raise tobacco taxes; offer cessation programmes; and ban advertising, promotion and sponsorship – globally speaking, only five out of 53 countries have implemented this last measure so far. It would be much more effective if all (and not just a few) European countries implement these measures, as the tobacco industry operates in a cross-border manner. Furthermore, smoke-free legislations should also include e-cigarettes, since it has been shown that they have similar health effects as cigarettes, containing nicotin, carbonmonoxyde and other carcinogens. Greece, for example, has already taken this step forward by deciding on same legal restrictions for e-cigarettes as those for traditional smoking when it comes to bans in public places and advertising.

In the USA, health groups have filed suit to expedite the FDA review of e-cigarettes, as this jeopardises the health of children by exposing them to addictive and flavoured tobacco products. In 2016, the US Surgeon General released a report concluding that e-cigarettes were unsafe for children and adolescents; findings from a systematic review published in 2017 suggested that e-cigarette usage by adolescents and young adults was associated with greater risk for subsequent cigarette smoking initiation.

We call upon countries to introduce a tobacco endgame strategy: reduce smoking to a low prevalence (for instance <5%) by a clearly stated target date (for instance, 2025). The tobacco plan in the UK and the “No Smoking Kids” campaign in the Netherlands could be taken as an example, as these plans aim to produce the first smoke-free generation, following a sequence of implementation steps.

In addition, professional societies could consider supporting legal actions against the tobacco industry, like the Dutch Paediatric Association has done in the Netherlands. As the industry specifically targets young people as replacement smokers, the blame is on the industry, not on the children who have been made addicted.

Finally, we as paediatricians can and should do more to prevent exposure of children to second- and third-hand smoke and to the temptations to start smoking. Discussion of tobacco use should become a regular topic during every consultation, even when the child doesn’t show any respiratory problems. Paediatricians and other physicians should actively encourage parents and children to quit smoking, and guide them towards coaching services that assist in quitting. This means that techniques like motivational interviewing should be formally trained during paediatric residency across Europe.

(Image Source: World Health Organization)

About the authors:

List of Authors

ANDREAS TROBISCH

ANDREAS TROBISCH is member of Young EAP. He is a paediatric trainee at the University for Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine in Graz, Austria.

LENNEKE SCHRIER

LENNEKE SCHRIER is the chair of Young EAP and the european junior doctor representative to the European Academy of Paediatrics. She is a 4th year paediatric trainee at the Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

VALENTINA FERRARO

VALENTINA FERRARO is member of Young EAP. She is a paediatric trainee and PHD student at the Department of Women’s and Children’s Health of the University of Padua in Italy.

RAFFAELA NENNA

RAFFAELA NENNA is the European Respiratory Society (ERS) representative within the European Academy of Paediatrics.

KÁROLY ILLY

KÁROLY ILLY is chair of the Secondary Care Council of the European Academy of Paediatrics. In addition, he is president of the Dutch Paediatric Society. He is a paediatrician at the Ziekenhuis Rivierenland Tiel in the Netherlands.