Interconnected care has for some time now made its way to the minds of people thinking about the future of modern healthcare. The concept of interconnected care has become widely used when policymakers and other stakeholders in care services are planning for the future of modern healthcare. The main problem is that the term interconnected care is too broad to be self-explanatory. This article aims to bring you closer to an understanding of both what the concept means, why it is increasingly important to incorporate in healthcare and also give some examples of what this looks like in pediatric care.

In 2009 WHO released a first report on Systems Thinking (1), which is the general idea underlying the concept of Interconnected care. Interconnected care is about linking every aspect of healthcare, ensuring that professionals and individuals have access to all the information and available services they need for an ideal treatment of patients (2). It is a tool that is meant to help us improve healthcare by creating a linkage and common understanding among the different stakeholders involved in providing healthcare. The most used clinical term for this is to ‘ensure a common understanding’- or a ‘shared goal’ for the provided care.

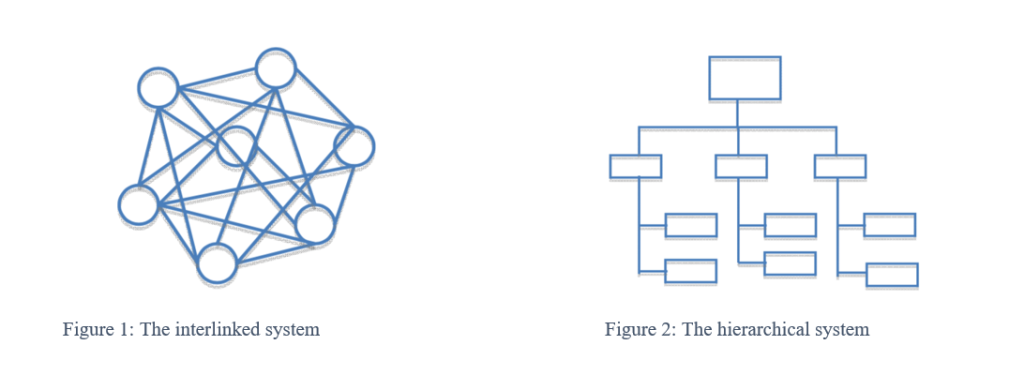

Visually you can imagine Interconnected care as a map that shows you involved stakeholders and how they are connected with each other. This stands in contrast, but not in dualism to, the traditional hierarchical form of providing healthcare services. Both models are shown underneath: in Figure 1 the interlinked system, in Figure 2 the hierarchical system (3). You can think of healthcare as a very complex machinery that only when having both systems working co-dependently will function at its’ most efficient.

USING THE METHOD OF ‘THE GOLDEN CIRCLE’ (4) TO EXPLAIN THE CONCEPT OF WHY, HOW AND WHAT

The underlying WHY of Interconnected care is that this approach enables us to improve modern standards of healthcare – not only on a local but also on a global level. Some examples of current WHATs are migrant health, mobile populations, changing environments, disease spread – communicable and non-communicable and digitization. We understand Interconnected care as the HOW, a concept that teaches us how to use what we have in order to improve the outcome when the situation is complex and dynamic. It is therefore crucial for stakeholders to sit down together, taking enough time to get familiar and connect over the issue before suggesting possible solutions. This means to think about how and with whom to get connected and have a clear identification and description of the WHAT before deciding how to tackle it. This will result in a practical map and the common knowledge of how to use and read it.

If the situation is static or very clear then linear approaches are still the chosen approach – the most use example here is the tackling of Acute medical conditions.

To give you an overview on how diverse interconnected care can or could be, we would like to describe two examples in the following:

- With the current pandemic situation members of the represented European countries of the EAP, junior and senior, sat down together to exchange on their experiences, insights and knowledge on COVID-19 in order to benefit from one another for the best possible care for children in the European member countries. The EAP RESOURCE CENTRE FOR COVID-19 (https://eapaediatrics.eu/covid-19-resource-centre/) was established and is continually updated. Webinars, blogs and coping strategies for children and their families during the time of isolation measures are featured on this site.

- The use of new technologies making patient relevant information accessible to those involved in one patients’ care could facilitate better healthcare and make it more efficient at the same time. If with the patients’ submission to hospital, person-related health information (patient history and diagnosis, medication, family history, risk factors etc.) was directly accessible to the health workers they could save a lot of time collecting data and rather spend it on their care. With the patients’ discharge from hospital, all the information on what was done and has to be looked after in the future could be transmitted to the responsible general practitioner or specialist in the outpatient setting automatically.

In light of the aforementioned, we can then reframe our view on healthcare and think about Systems Thinking in a more dynamic manner. As a self-organized system where we need to be aware of the possibilities that lie in each part.

Interconnected care includes:

- Identifying all stakeholders being involved in providing healthcare to people (The WHO has defined “The six building blocks of a health system” that can help with the comprehensive identification of stakeholders: health services, health workforce, health information system, medical products/vaccines/technologies, health financing and Leadership/ governance (5)

- Learning more about their role and responsibilities

- Finding synergies among stakeholders

- Sharing knowledge and experience for the better of the patients

- Collecting challenges and obstacles that we are facing in providing healthcare and think about ways of how connecting with each other can help us improve

- Applying this approach not only to clinical practice but also to other areas of healthcare such as research and the development of medical devices

- Allowing technical innovation to help us improve the healthcare provided

- And lastly making data and knowledge on health more accessible to our patients

HOW DOES THIS AFFECT CHILDREN AND WHAT SHOULD BE DONE?

Pediatric patients often come along with diverse challenges, interests and needs due to the colorful interaction between their families, their social environment and their individual needs that all have to be addressed equally and underline the importance of a more holistic and interconnected approach. Children of today grow up in an increasingly globalized, moving world with mobile populations and a high level of interconnectivity between people living on different continents of the world. These circumstances all come along with different challenges in healthcare that can best be addressed by Interconnected care. From a child’s perspective it must therefore only be sensible to establish the concept of Interconnected care in healthcare.

Especially with rare diseases Interconnected care becomes inevitable in the light of the often small numbers of patients with one condition that emphasizes the need for close cooperation, the exchange of knowledge and experience and synergies in research.

Topics that should also be addressed by the concept of interconnected care are prevention and public health matters. Prevention starts with conception, continues its way during pregnancy when fetal programming is creating the first influential environment for later life and is of great importance for every human being for example in order to avoid unnecessary chronic conditions, identify and contain future outbreaks of communicable diseases.

Another under-represented area of healthcare is the public health sector that would also benefit from more interconnectivity, thereby helping to provide better patient and community-centered care – and not only in a pandemic as we are facing it at the moment. A steadier utilization and distribution of resources could be a result from vivid interconnectivity among stakeholders.

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

In order to bring Interconnected care into practice we summarize our main recommendations in the following:

- Analyze the challenges and obstacles you are facing in your working environment carefully and try to define them as precisely as possible

- Reach out and get in touch with people, disciplines and stakeholders involved in this in order to discuss matters openly and get to the root of things keeping mapping in mind

- Look for a suitable forum to connect and propose possible solutions to your problem, accessible to others who might be facing the same situation, find synergies and partners for future collaboration

- Use the interaction with other stakeholders to learn about other innovative ideas and be open to new, smart technologies: Data and devices have been the tool to improve medicine for a long time, advanced health monitoring can help reduce hospitalization and interventions (2)

- Not only think about current challenges in your patients’ well-being, consider future hazards especially under the circumstances of mobile populations and how these could be addressed: Examples could be the support of home environments which is especially crucial in a pandemic situation (6) and the use of health data

- Bring the children’s perspective into light. With children having all their life still ahead of them, especially when suffering from chronic conditions, they are the ones to benefit most from the concept of Interconnected care. Empower them to take an active part in their own health and healthcare and teach them how to promote health more independently by technological innovation and thorough more patient involvement

- Let the concept of Interconnected care help to foster glory in prevention

About the authors:

List of Authors

Lena de Maizière

Lena de Maizière represents the German pediatric trainees within Young EAP. She is a 4th year paediatric resident.

Karen Daehlin Holm

Karen Daehlin Holm represents the Norwegian pediatric trainees within Young EAP. She is a 3rd year pediatric resident, currently doing a year side-specializing in child- and youth mental health.

References

- Don de Savigny and Taghreed Adam (Eds). Systems thinking for health systems strengthening. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO, 2009.

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/wellbeing/future-health/connected-healthcare/

- The art of Hosting Workbook 2013, Karlskrona University, Training in the art of hosting and the art of harvesting conversations that matter

- How great leaders inspire action, TED talk by Simon Sinek, September 2009, https://www.ted.com/talks/simon_sinek_how_great_leaders_inspire_action/transcript?language=en

- Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. ISBN 978 92 4 159607 7 (NLM classification: W 84.3), © World Health Organization 2007

- Mirco Nacoti, MD, Andrea Ciocca, MEng, Angelo Giupponi, MD, Pietro Brambillasca, MD, Federico Lussana, MD, Michele Pisano, MD, Giuseppe Goisis, PhD, Daniele Bonacina, MD, Francesco Fazzi, MD, Richard Naspro, MD, et al., At the Epicenter of the Covid-19 Pandemic and Humanitarian Crises in Italy: Changing Perspectives on Preparation and Mitigation, NEJM Catalyst, March 21, 2020.