At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was uncertainty with regards to how badly children would be affected by the novel coronavirus. We feared the worst but hoped for the best and the latter seems to have come out on top. The clinical symptoms are usually milder than by adults and paediatric hospital admissions are rare.

In many ways Iceland was unique in its approach to the responses to the pandemic. The public health authorities were well prepared having watched the epidemic storm through China and later European countries. From early on, daily televised press conferences were held by the Chief Epidemiologist, the Surgeon general and the head of the national police department (never has a politician been present!) and is watched by an overwhelming majority of the nation.

The measures taken were based on the plan of massive testing, putting those who tested positive in isolation and all who were exposed in quarantine for 14 days. In addition, a private company Decode genetics offered to test asymptomatic people for free. Taken together this led to 46.000 tests (14% of the population) 19.000 people (6% of the population) have been put in quarantine and 1800 infections with 95% of them traced (it was known from whom they were infected and more than half was already in quarantine). Also, it was noted that only few asymptomatic infections were roaming free in the population (<1%). Interestingly of the around 1000 children younger than 10 years who were tested without symptoms, none were positive. Furthermore, we could also deduct that none of the 1800 cases were infected by a child < 10 years of age whereas infections from adults to children were quite common.

With this knowledge in mind, there has been no closure of schools nor day-care centres although they have been running on a limited power also due to staff issues.

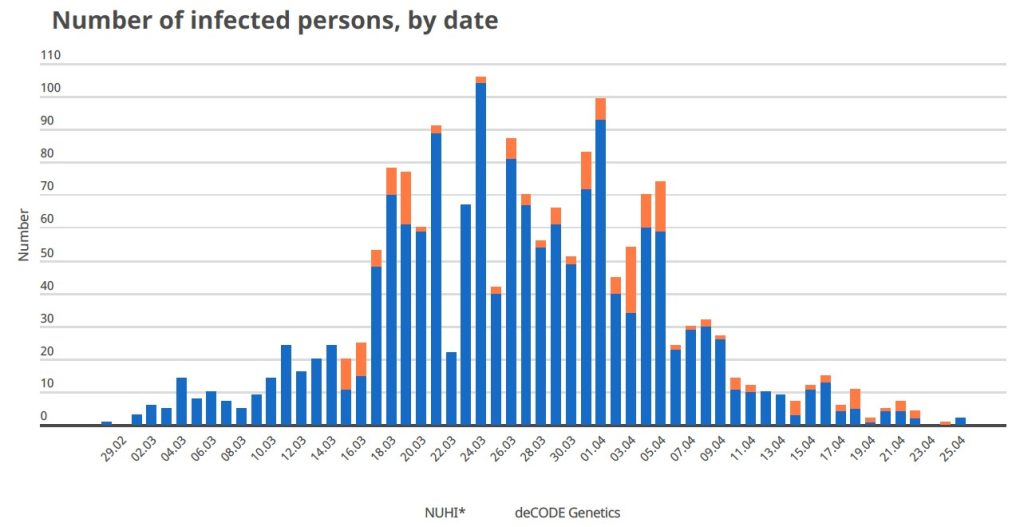

Sooner than was anticipated, the epidemic has come to a halt (very few cases diagnosed per day for the last 5 days, see figure).

Fewer than 200 children were infected but none needed hospital admission although they were rigorously followed up by telephone (every 1-2 days) while symptomatic.

To summarise, the Iceland approach was to react in time and escalate measures as the epidemic surged, but all decisions were made based on the available data (and not emotion). Excellent communication between the health authorities and the public where all decisions were made clear a few days in advance. The three people running the press conferences are now rated as the most popular people in Iceland! The endgame is now in hand and considering that only a small proportion of the population has been infected, the risk of resurgence of infections is high and restrictions are likely to remain in place for the remainder of this year causing catastrophic situations for the tourist industry and the economy of Iceland. One can only hope that the next wave of infections (which is likely to come) will also spare young children.

About the author:

Valtýr Stefánsson Thors

Valtýr Stefánsson Thors (Iceland) is the President of the Icelandic Paediatric Society

New ways to test high-risk medical devices.

Manufacturers of medical devices need to test their products before being allowed to market them. Specifically, they require clinical data showing their medical device is safe and efficient. In this context, the EU-funded CORE-MD project will translate expert scientific and clinical evidence on study designs for evaluating high-risk medical devices into advice for EU regulators. The project will propose how new trial designs can contribute and suggest ways to aggregate real-world data from medical device registries.

It will also conduct multidisciplinary workshops to propose a hierarchy of levels of evidence from clinical investigations, as well as educational and training objectives for all stakeholders, to build expertise in regulatory science in Europe. CORE–MD will translate expert scientific and clinical evidence on study designs for evaluating high-risk medical devices into advice for EU regulators, to achieve an appropriate balance between innovation, safety, and effectiveness. A unique collaboration between medical associations, regulatory agencies, notified bodies, academic institutions, patients’ groups, and health technology assessment agencies, will systematically review methodologies for the clinical investigation of high-risk medical devices, recommend how new trial designs can contribute, and advise on methods for aggregating real-world data from medical device registries with experience from clinical practice The consortium is led by the European Society of Cardiology and the European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, and involves all 33 specialist medical associations that are members of the Biomedical Alliance in Europe.