This is the fourth in a series of Dr. Rob Ross Russell’s brief musings on aspects of the COVID-19 crisis.

They are all my personal views and should not for a moment be interpreted as advice or dogma – nor am I in any way seeking to undermine the national advice that is issued, but rather to reflect on some of the issues and verbalise some of the questions and thoughts that I have had.

For those that missed the first three, they can (should they wish) find them here, here and here.

In this piece I am thinking about the children – as a paediatrician that seems pretty appropriate, but there have been some unusual features, and perhaps hidden concerns.

The first notable issue is that they seem to be far less affected by this particular infection than you might expect. To date there have been no deaths in children under 10, and the mortality in older children is also very low. A paper published in Lancet Respiratory has set out to address the characteristics of the disease in children, but seems to shed little light on the reasons why children are relatively spared. It does reference a pre-publication article in Paediatrics that reviewed over 2000 children with COVID19. They note the relatively mild nature of the disease and suggest 2 or 3 possible reasons – less ACE-2 binding (the route by which coronavirus probably enters cells), better paediatric exposure to other respiratory viruses such as bronchiolitis (RSV), and a rather vague comment about a ‘maturing’ immune system.

There was a suggestion in the data, and in commentary on that, that perhaps infants did worse than older children – at least in terms of getting more severe disease, but the data relies heavily on who was tested and needs to be treated with great caution. Either way it is clear that infected children are still able to transmit the disease to others. Whatever the truth, this aspect of the pandemic is interesting and may yield useful clues about the disease itself.

However, of rather more interest is perhaps the way in which children are losing out as a result of the policies being enacted to deal with this crisis. Paediatricians are beginning to voice concerns at the impact of this pandemic on the weel-being of children throughout the world.

Allocation of resources: I suppose it is inevitable that as space within the hospitals is overwhelmed, then all areas will be involved, but nevertheless, the disruption of paediatric wards and intensive care units to ensure adequate space for adult patients should be causing us some concern. In my hospital, the paediatric area of the Emergency Department has been taken over, moving children to a separate (and less well equipped) part of the hospital. There have been discussions about admitting young adults up to the age of 25 on to Paediatric Intensive Care Units (PICUs). The latter has been endorsed after careful consideration by the PIC Society and Adult IC Society, and I applaud their co-operative working. However the impact on the ‘normal’ caseload must be assessed. Paediatric surgery is being cancelled. Many clinics are cancelled – care for children with chronic conditions is affected and their health may suffer.

Pulling together and supporting all services is essential, and I am as keen as anyone to support colleagues in trouble whatever their specialty or area. But let us also acknowledge that we are disadvantaging our children in doing so.

Routine care is being disrupted: Not only is hospital care being affected, but of greater concern is the effect of the pandemic on routine healthcare for children. The WHO regional office for Europe has issued a statement calling for routine vaccinations to be continued in children, but a number of countries are now talking of stopping their program in the light of concerns over cross-infection and workload. UNICEF has warned of a fall in vaccination rates, and especially of concerns in countries such as Syria or Afghanistan, where outbreaks of vaccine susceptible diseases may well emerge. Even in the UK, balancing self-isolation against a routine visit to the GP, makes for a difficult choice for families.

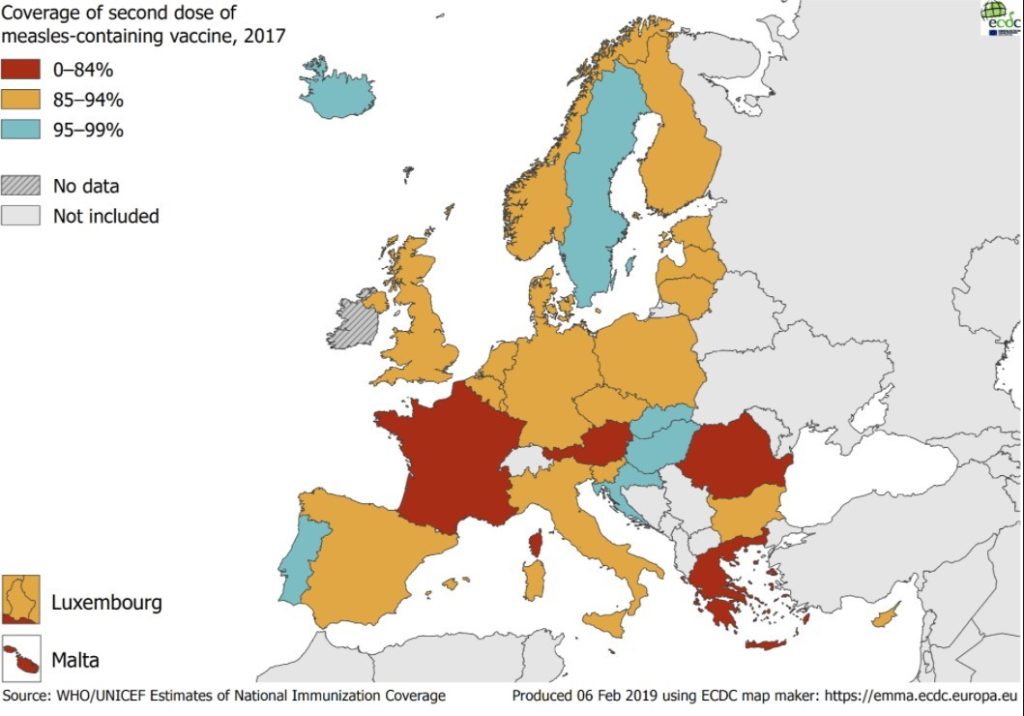

Our coverage in the UK (and most of Europe) is good enough that a delay of a few months in vaccination will not make a major difference. But rates of measles vaccination have fallen a lot over the last few years and so outbreaks of the disease are already more common than they were, given that 95% coverage is needed for proper immunity:

Similarly, routine developmental checks, and baby checks are being reduced. These provide an essential screening test for childhood conditions such as deafness, CDH and many other conditions. At present in the UK these seem to be continuing, but in other countries such care is being postponed, and the risk of serious conditions being missed – with lifelong effects – is concerning.

Schools: The disruption to education is enormous. And of course school is about a great deal more than French and Maths – the social skills learned by children in playing and interacting with their peers are critical. Not only that, but by closing schools we oblige parents to provide childcare, and that takes a large section of the workforce (especially women in healthcare for example – most of our nurses!) away from their jobs. I am all for protecting teachers, but I am also all for protecting healthcare workers, but don’t suggest we should close the hospitals… I do remain concerned that school closure may be a measure that is more costly than beneficial.

We are spending their future away: Most concerning to me is that in the rush to keep the electorate happy, the governments of the world are spending their children’s future. The level of spending is almost unprecedented, certainly sonce the second world war. A useful short summary by the Institute of Fiscal Studies suggests a shrinkage in GDP of 5% this next year adding a further £70bn to the debt. This is debt our children will inherit and it causes me enormous concern that we are quite so content to spend it now. I have no clear options for what else we should do but it remains a huge worry.

About the author:

Rob Ross Russell

Rob Ross Russell (UK) – is the Director of Medical Studies at Peterhouse, University of Cambrigde. He is also the current Chair of the European Board of Paediatrics. Rob works at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, where he has been a consultant in Paediatric Intensive Care and Paediatric Respiratory Medicine.

New ways to test high-risk medical devices.

Manufacturers of medical devices need to test their products before being allowed to market them. Specifically, they require clinical data showing their medical device is safe and efficient. In this context, the EU-funded CORE-MD project will translate expert scientific and clinical evidence on study designs for evaluating high-risk medical devices into advice for EU regulators. The project will propose how new trial designs can contribute and suggest ways to aggregate real-world data from medical device registries.

It will also conduct multidisciplinary workshops to propose a hierarchy of levels of evidence from clinical investigations, as well as educational and training objectives for all stakeholders, to build expertise in regulatory science in Europe. CORE–MD will translate expert scientific and clinical evidence on study designs for evaluating high-risk medical devices into advice for EU regulators, to achieve an appropriate balance between innovation, safety, and effectiveness. A unique collaboration between medical associations, regulatory agencies, notified bodies, academic institutions, patients’ groups, and health technology assessment agencies, will systematically review methodologies for the clinical investigation of high-risk medical devices, recommend how new trial designs can contribute, and advise on methods for aggregating real-world data from medical device registries with experience from clinical practice The consortium is led by the European Society of Cardiology and the European Federation of National Associations of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, and involves all 33 specialist medical associations that are members of the Biomedical Alliance in Europe.